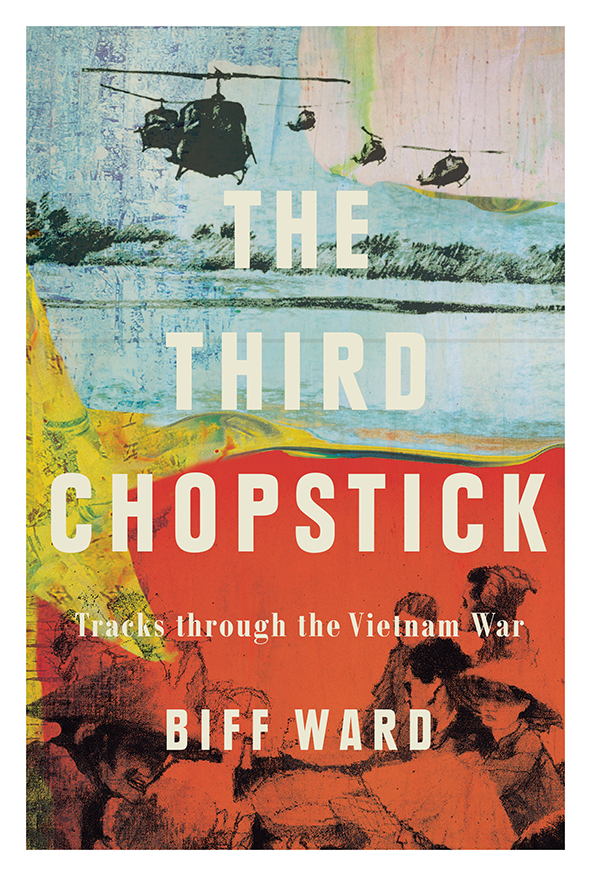

The Third Chopstick: Tracks through the Vietnam War

- The Beagle

- Apr 22, 2022

- 3 min read

The Third Chopstick: Tracks through the Vietnam War

THE VIETNAM WAR ROCKED AUSTRALIA TO ITS CORE... By Biff Ward

The Third Chopstick transports us back to those days. In starkly beautiful prose Biff Ward, herself a protester, seeks to understand the war from multiple angles. She balances the heartfelt motivations of the protest movement with candid accounts from veterans about what was happening for them in Vietnam and afterwards. In riveting interviews, she explores combat, the ravages of PTSD, and the acceptance that can come with ageing and peer support. She also takes us to the peaceful Vietnam of the post-war years, capturing poignant images of the aftermath of what they, of course, call the American War. Her lyrical evocation of the people she meets and war sites she visits render the war in a new light. The Third Chopstick is the profoundly moving story of one woman's passion to bear tender witness to those involved in that tumultuous time. A must-read for all the Vietnam generation, their descendants and friends. Peter Yule, author of The Long Shadow, said, I have been studying the impact of the war on the lives of Vietnam veterans for many years and I learnt more from this book than any other I have read.

BOOK DETAILS

Published: 2022

Trim size: 6 x 9

Page count: 330

Internal pages: B&W

Binding: Paperback

The Third Chopstick ebook versions:

Please visit this page for information on downloading your ebook to your device or app: https://themoshshop.com.au/pages/downloading-your-ebook-to-your-device-or-app

Prologue

“My cousin Hugh was an Australian soldier in the Vietnam War. I interviewed him more than twenty years after he was there. He told me that being on patrol meant having no idea where you were or where you were going and that he found this deeply disturbing. He worked out that the only way to know what was going on was to carry the wireless set on his back because the platoon commander just grabbed it to talk to HQ or other units.

No one else wanted the job because the radio weighed over twenty-three pounds – ten and a half kilos in today’s terms – but Hugh put his hand up.

It meant he got to hear everything that was said, including where they were.

While Hugh was carrying his pack and gun and the heavy radio in the stifling heat and monsoonal rains of Vietnam, I was painting Stop the War placards on my dining table, standing beneath Viet Cong flags at demonstrations and raising my chanting voice at every opportunity. I kept it up in one form or another until that surreal ending, the fall of Saigon in April, 1975.

Decades later, along an unanticipated path, I became fascinated by Vietnam veterans. I wanted to know what the war had been like for them, the detail of what they had experienced. One I befriended was Ray Fulton, a national serviceman who had been a twenty-year-old carpenter called up against his will to serve two years in the army.

While I was demonstrating, Ray was bedecked with the military paraphernalia of an Australian infantryman, patrolling through the scrub and villages of Phuc Tuy Province where he was charged with overseeing the movements of the people who lived there, who had their homes and rice paddies there. At gunpoint, if necessary.

When I met him in 1998, he was working tirelessly to help other veterans, mainly by setting up systems so that they could get their entitlements. In the intervening years, he told me that he’d had been spectacularly alcoholic, homeless, crazed, in gaols and psych wards but was now doing okay, thanks to Alcoholics Anonymous.

He spoke often in elliptical snippets, bewildering outbursts or questions, such as ‘What is death anyway?’, delivered in a belligerent tone. I was always stumbling to unpack his wild words, to plumb his secrets. He was so charismatic and so volatile that he came to represent for me a kind of archetypal veteran. After his death I was given his own account, some seventy pages of his handwriting, outlining what had happened to him in Vietnam. Even as I gained some understanding of his exquisite agony, I felt there was a piece missing. Gradually I accepted that his story would always be incomplete in some way that I couldn’t discern.

Years after Ray died, it turned out that the answer was closer to me than I could ever have dreamed. Cousin Hugh. In phone conversations across the country, Hugh in Esperance, me in Canberra, it turned out that he held the missing piece of Ray’s story even though they’d never met. On a wave of serendipity, our words lit up tracks which had not been visible before.

Hugh and I joined links in the tragic chain of events that had engulfed Hugh’s close friend John McQuat, Hugh himself and my friend Ray.

Closing the circle, we spoke in sounds that were soft to the ear, because the story was so sad and our hearts so full.”